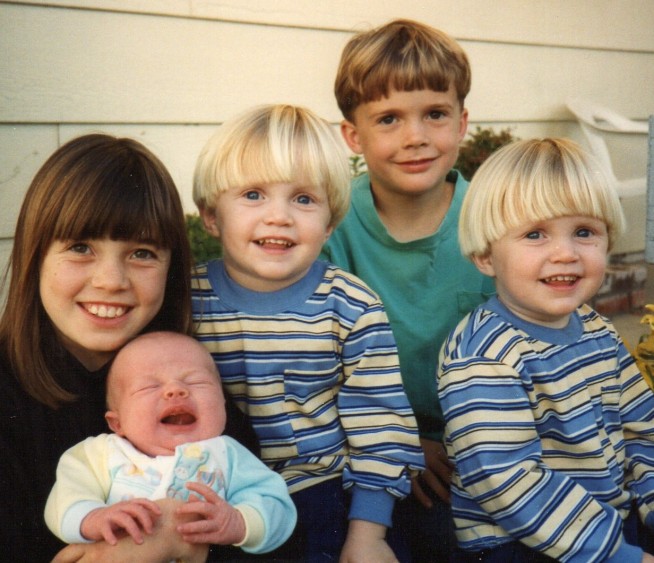

*The photo above is of my four younger brothers and me in 1994.

In seventh grade science, we created babies by flipping coins. The assignment had to do with genetics, and I remember drawing a child with my lab partner as we determined characteristics category by category: green eyes, brown hair, a small nose, dimples. Later, we cared for hard-boiled egg babies. I rescued one child, who had been abandoned by a careless boy, and fixed the cracks in the shell with tape. My girlfriends and I talked about the kinds of mothers we would be as we made tiny dresses from felt. We would bake pies, build blanket tents, and read picture books every night.

As a twenty-four year old, I sat in the hospital conference room and watched the rain streak the windows. I couldn’t stop thinking about those fantasy children—all the years’ worth of make-believe babies. The coordinator of the fertility study came into the room carrying an armful of pamphlets. He passed them out to my mom, to me, and to the man who was still my husband at that time. We stared silently at the glossy brochures.

“We know that fertility is a main concern to young women undergoing chemotherapy, and to their families as well. Even women who are single want to ensure their futures,” the coordinator explained in a dry voice as he nervously adjusted his glasses. I imagined them—all of these young women sitting with their mothers and finding comfort in the idea that their eggs could be sliced out and frozen indefinitely. My own mom already referred to her fictitious granddaughter as Olivia. She picked up things in the store and casually mentioned how Olivia might like this or that. The coordinator kept talking about quality of life and returning to normal. I wonder how many mothers and daughters had placed their hopes in his study.

I knew about mothers who were terrified of losing their daughters or having them returned broken beyond repair. Growing up in oncology wards, I had watched the slow process of parents losing their children and would later watch children losing their parents.

I’d watch both my mom and dad lose their fathers to cancer. “Nothing will ever be okay again,” my mom said days after my grandfather died, as she felt her family falling apart.

Still, I didn’t want to hear this man’s promises.

A recent dose of chemotherapy had sent me into anaphylactic shock. As my senses rapidly shut down, the last thing I saw was my then-husband standing in the doorway—frozen in fear, face drained, and looking no older than the day we started dating at seventeen (a year after my first cancer treatments). Toxins still throbbed in my veins, and I had the prospect of another lung surgery (my fourth) looming. I pushed the pamphlet back.

“No,” I said. Everyone in the room looked at me in surprise. “No, thank you. I don’t want you to cut up my body anymore. I don’t want my parents to pay for bits of me to sit in hospital freezers. I’ll adopt.” I stood to go, feeling a rush of conviction. The coordinator stared, completely baffled. He was offering me the best in medical technology. He was offering me “normal,” a chance to protect the very thing that made me a woman, and I was turning him down. After all, every woman’s magazine seemed to be running articles praising our newfound ability to control our biological clocks. Was I the first in the line of heartsick mothers and daughters to walk away from this opportunity?

Up until that moment, I hadn’t given much thought to adoption. But as soon as the thought came to me, it made perfect sense. From the moment I could babysit, I had worked and volunteered in childcare and education. I had witnessed how families work and had seen plenty of situations where natural birth and blood couldn’t make up for negligence. I had loved and nurtured so many children (including my four younger brothers) that I had no doubt I could love any child sent to me to raise. My mom’s parents had spent their lives opening their home to children and lost souls of all ages. The genetics had no more meaning to me than the day in seventh-grade science class when we determined them with a penny and some colored pencils.

And I felt a vague sense of being insulted by this coordinator’s belief that I needed his help, his study, and his technology to feel like a woman and a mother.

Later, when my health was restored, I began researching adoption and fostering. I discovered preexisting conditions like my amputation and my then-husband’s heart defect would make adoption extremely complicated. I still didn’t lose faith. I knew a baby would come. And even though my body seemed to be functioning “normally” (much to the surprise of my oncologist and thanks to my plant-based diet), I was attached to the idea of adoption.

A chance for a baby did come. A woman we knew through a mutual friend was considering abortion unless she could find a couple willing to take her baby. It felt like fate, like destiny, like the universe working in its mysterious way. I treasured the idea for several weeks without telling anyone besides my mom.

We knew it was foolish, but we couldn’t help dreaming up a nursery with a jungle theme—light green walls, stuffed elephants, giraffes, and monkeys, and a calm night sky painted on the ceiling. I could almost feel the tiny fingers curling around mine and almost smell the milky sweetness of the baby’s head. I didn’t tell my then-husband about the baby until after the mother had gone through with the abortion in order to go back to her other child’s father. My then-husband still said no to the baby that no longer existed.

Whenever there is a loss in my life, I create.

I wrote a short screenplay about a couple with preexisting conditions struggling to adopt and to overcome others’ beliefs that their disabilities disqualify them from becoming parents. I asked my husband for a divorce, and he admitted he never wanted to have children.

I thought of the day with the glossy pamphlets promising a future through medical science and realized that, even though I had walked out, I was still holding onto some version of that dream. I still wanted a picket fence.

I took a deep breath and let go of my idea of how my life should look. I opened my mind to a broader definition of family. I decided then and there not to spend my life mourning the loss of something I never had. I thought of the left-behind egg baby I pieced back together with scotch tape and made a vow to love whoever came into my life needing that care.

While working on the short film, two members of our indie crew were preparing to become fathers. They both scrambled to ready themselves for the unexpected transition. To me, it seemed like a good omen. Instead of feeling jealous, left out, or discouraged, I felt amazed at how fragile our versions of reality can be. It takes so little to bump us off the tracks of our expectations and into a wilderness of possibility. I am not where I expected to be at this point in my life. Instead of raising a family, I am discovering how long it takes one person to eat a pack of spaghetti. But, honestly, there is something wonderfully freeing to knowing that there is more to the world than I can grasp with my limited perspective.

So much of love is advertised to us in the form of ownership—the promise of forever.

But love can’t be guaranteed with a ring or a freezer full of genetic material or a lifetime of hope. Love is an action that must be renewed daily. It can’t be bottled up and stored away. It can’t be controlled by religious institutions or sold in stores. It must be practiced and given without any assurance of return. And, luckily for me, it is an endless source. The supply will never run dry. No matter where I end up or what I lose along the way, I can’t be separated from my ability to love.

So, I opened the floodgates and began to give without regret to children who are not mine, to people who are not mine, to a world that is not mine to keep.

Danielle Orner is a writer, actress, motivational speaker, yogi, vegan, cancer survivor, and amputee. Diagnosed with bone cancer at age fifteen, she spent a decade getting scans, surgeries, and chemotherapy treatments. Three years ago, she decided to take an active role in her health researching anti-cancer lifestyles. Currently, she is cancer-free. She doesn’t wait for the six-month scan to tell her she can start living. She’s too busy making impossible things possible. To learn more about Danielle, follow her on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube.