In the 1960s and 1970s psychologist Walter Mischel conducted a series of studies that came to be known as the Stanford Marshmallow Experiments. In the studies, children were given the choice between two options: 1) They could have an immediate reward (a marshmallow, cookie, etc.) or 2) They would be given two rewards (often another marshmallow) if they waited until the experimenter returned to the room (after an absence of around fifteen minutes).

During the experimenter’s absence, the child would be left sitting face-to-face with their temptation (the marshmallow). Some children would eat the marshmallow as soon as the experimenter left, while other children were able to wait until the experimenter returned so that they could enjoy two rewards.

The ability of children to wait to eat the marshmallow became known as “delayed gratification,” and studies conducted in the decades since these original experiments have shown that children who are able to delay gratification tend to have better life outcomes, as measured by factors such as SAT scores, education level and even body mass index thirty years later.

Scientists have replicated the delayed gratification studies using all kinds of populations and all types of rewards, and the general result seems to be the same.

People who are able to hold off on their impulse for immediate gratification generally tend to do better in other areas of their lives.

I think that this finding stems partly from the fact that North Americans live in a very structured society, where following your impulses on a whim doesn’t really jive with how we want people to behave. Consider the modern-day school system, for example. From a very young age you are taught to sit still, listen to the teacher, and obey a bell like it’s a god. If you question these ideas or behave in a way that’s out of the box, you are typically reprimanded – or worse, diagnosed with a disorder like ADHD. And while I agree that it’s important that we aren’t all running around like wild animals, indulging in our every whim, I think as a society we’ve taken the whole delay of gratification thing a little too far.

When I first learned about the marshmallow experiments as an undergraduate student in Psychology, I immediately wondered what my six-year old self would have done. Would I have indulged in the marshmallow right away, or would I have waited for an even better reward? I know exactly what my adult self would do. I would probably not only wait fifteen minutes for the better reward – I would take the two marshmallows, put them in my pocket, and wait for an even better third reward. Of course, there is no third reward, so the marshmallows would get hard and stale, leaving me without anything to enjoy.

What I’m getting at here is that throughout my adulthood, I’ve become a sort of delayed gratification Olympian.

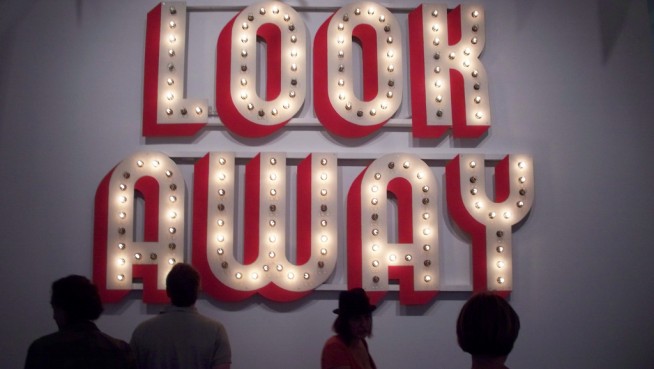

I delay gratification so much that I sometimes deny myself pleasure – a habit that I’d like to give up. @BethanyButzer (Click to Tweet!)

On the one hand, my ability to delay gratification has brought me some success. For example, I was able to resist the impulse to party every night during college so that I could spend ten years getting my PhD. As an entrepreneur, I was able to deny my urges to ditch work so that I could be productive.

The problem is that over the years I started to see my ability to delay gratification as a sort of badge of honor, to the point that I feel like I don’t deserve pleasure unless I’ve denied it from myself first. So when my husband asks if I’d like to go for ice cream on a Wednesday night, my mind immediately starts to tally up whether I “deserve” the ice cream. Have I worked hard enough this week? Did I budget my money well last weekend so that I can afford treats during the week? Do I really have time for ice cream, or should I be doing something more productive?

I realize that this line of thinking sounds ridiculous, but it seems to be deeply ingrained in my psyche. I’ve even noticed that my favorite part of any pleasurable experience is often not the pleasurable experience itself. It’s the part right before the experience – where I know that I’ve worked hard enough and denied myself enough to “deserve” the pleasure that’s about to come. It’s kind of like the difference between enjoying a Friday afternoon versus a Sunday morning. On Friday afternoons I typically feel great because I know that I’ve put in a solid week of work (where I denied myself pleasure) and that I have fun events coming up for the weekend. On the other hand, when I’m lounging around and taking things slowly on a Sunday morning, I often feel guilty for enjoying myself.

In the past, the one thing that often released me from the grip of delayed gratification was alcohol. As is the case with most people, alcohol lowered my inhibitions, released my guilt over experiencing pleasure, and often led me to go after exactly what I wanted without inhibition. But this isn’t exactly a healthy way to enjoy pleasure!

These days my goal is to give myself permission to experience pleasure – no strings attached (and without alcohol as an aid). As long as I’m not hurting anyone or doing anything ethically reprehensible or illegal, then I think this is ok. But it’s a constant process of dealing with the voice in my head that tells me I need to delay gratification by putting the marshmallows in my pocket for so long that they become inedible.

How do you experience pleasure? Do you go for immediate gratification, or do you control your impulses? Do you have a healthy relationship with pleasure, or do you feel guilty when you do things that make you feel good? I’d love to hear from you in the comments below!

Bethany Butzer, Ph.D. is an author, speaker, researcher, and yoga teacher who helps people create a life they love. Check out her book, The Antidepressant Antidote, follow her on Facebook and Twitter, and join her whole-self health revolution.

If you’d like tips on how to create a life you love, plus some personal instruction from Bethany, check out her online course, Creating A Life You Love: Find Your Passion, Live Your Purpose and Create Financial Freedom.

Image courtesy of martinboz.